Full Citizens Coalition (FCC) is a Connecticut-based action group focused…

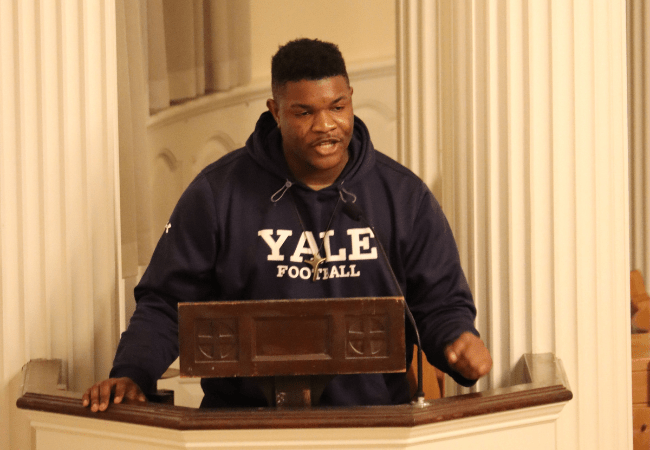

As the son of a servicewoman and the grandson of a Black Panther, Noah Humphrey ’23 M.Div. has always been dedicated to service and advocacy. On the Hawaiian island O‘ahu, for instance, Noah is involved with the organization Kalihi Valley Instructional Bike Exchange (KVIBE), which offers bikes and training to youth in Kalihi–work that is extremely important to Noah. “I believe that our purpose, design, and mission involve healing, which is a major part of what I want to introduce into my work,” he explained.

Since arriving at Yale Divinity School in 2020, Noah has continued this work in many ways. As a Volunteer Coordinator for Dwight Hall, he hopes to build bridges between KVIBE and Yale, so that the knowledge he discovers with KVIBE can reach Yale and Yale’s resources can reach KVIBE. “I want to incorporate [KVIBE’s] values into Dwight Hall and the facilities around Yale and New Haven. I believe that the work they are doing should be credited, and I want to build a connection between the kids in Kalihi and Yale in terms of finances, educational resources, and all that I can get for them over there,” Noah said.

At Yale, much of his activism has centered around the Pennington Legacy Group, an organization he founded to remember and honor Rev. Mr. James W.C. Pennington, the first Black student at the Yale Divinity School. Though Edward Bouchet is celebrated as the first Black graduate from Yale College, in an article for the Yale Daily News, Noah explained that decades before Bouchet graduated in 1874, Rev. Pennington was a student at Yale’s Divinity School from 1834 to 1839. Because he was not allowed in Yale classrooms, Rev. Pennington listened to lectures from outside the buildings. However, unlike Bouchet, Rev. Pennington was never awarded a degree because of racist Yale University policies that barred Black students from matriculating for a degree.

“I couldn’t accept that,” Noah said. “I felt it was insane that James Pennington, the first [B]lack student at a liberal school that pledges itself to truth and justice, didn’t receive his rightful degree.”

The Yale Black Seminarian Council advocated for many years for Pennington to be awarded a degree, but Yale maintained its stance that it did not award degrees posthumously. Upon his arrival to Yale, Noah began working to overcome this policy and convince Yale to award the degree Pennington deserves.

Along the way, Noah faced strong resistance from many in the Yale administration. “I faced significant challenges in obtaining James Pennington’s rightful degree from Yale, with little support from higher-ups who claimed they wanted to help but cited legal constraints as a reason for inaction. Despite this silence and lack of action, I was determined to find ways to overcome the obstacles,” he said. In his advocacy, Noah did extensive research on Pennington, spoke to leaders and community members in Yale and New Haven, and finally, at the urging of Martin Luther King III, in January 2023 he founded the Pennington Legacy Group.

After months of advocacy from the Group, Yale finally awarded a posthumous degree to Pennington as well as to Reverend Alexander Crummell, another Black man who studied at Yale in the 1800s but was denied a degree because of his race. In fall 2023, Yale plans to host a ceremony to celebrate these two students and remember the injustices they and other Black Americans faced while students at Yale.

However, Noah emphasizes that his social activism is far from over. “There are still many injustices to address, not only in academia but also in the New Haven community. Homeless outreach centers and other community-based initiatives that prioritize health and reach those in need require greater funding. Although Yale’s $65 billion endowment is impressive, a donation of around ~$135 million over several years is insufficient…It’s crucial to consider where resources should be allocated and what truly matters.”